أجزاء أعجبتني من كتاب (عن الكتابـة) للروائي الأمريكي "ستيفن كنج"، أحب أن أنشرها هنا لتكون بمثابة خُلاصة الكتاب بالنسبة لي، و لمشاركتها مع من يُحب الاستفادة منها.

-1-

The next level is much smaller. These are the really good writers. Above them—above almost all of us—are the Shakespeares, the Faulkners, the Yeatses, Shaws, and Eudora Weltys. They are geniuses, divine accidents, gifted in a way which is beyond our ability to understand, let alone attain. Shit, most geniuses aren’t able to understand themselves, and many of them lead miserable lives, realizing (at least on some level) that they are nothing but fortunate freaks, the

intellectual version of runway models who just happen to be born with the right cheekbones and with breasts which fit the image of an age.

-2-

If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot. There’s no way around these two things that I’m aware of, no shortcut.

I’m a slow reader, but I usually get through seventy or eighty books a year, mostly fiction. I don’t read in order to study the craft; I read because I like to read. It’s what I do at

night, kicked back in my blue chair. Similarly, I don’t read fiction to study the art of fiction, but simply because I like stories. Yet there is a learning process going on. Every book you pick up has its own lesson or lessons, and quite often the bad books have more to teach than the good ones.

-3-

You may find yourself adopting a style you find particularly exciting, and there’s nothing wrong with that. When I read Ray Bradbury as a kid, I wrote like Ray Bradbury—everything

green and wondrous and seen through a lens smeared with the grease of nostalgia. When I read James M. Cain, everything I wrote came out clipped and stripped and hardboiled.

When I read Lovecraft, my prose became luxurious and Byzantine. I wrote stories in my teenage years where all these styles merged, creating a kind of hilarious stew. This sort

of stylistic blending is a necessary part of developing one’s own style, but it doesn’t occur in a vacuum. You have to read widely, constantly refining (and redefining) your own

work as you do so. It’s hard for me to believe that people who read very little (or not at all in some cases) should presume to write and expect people to like what they have written, but I

know it’s true.

-4-

The real importance of reading is that it creates an ease and intimacy with the process of writing; one comes to the country of the writer with one’s papers and identification

pretty much in order. Constant reading will pull you into a place (a mind-set, if you like the phrase) where you can write eagerly and without self-consciousness. It also offers you a

constantly growing knowledge of what has been done and what hasn’t, what is trite and what is fresh, what works and what just lies there dying (or dead) on the page. The more

you read, the less apt you are to make a fool of yourself with your pen or word processor.

-5-

My own schedule is pretty clear-cut. Mornings belong to whatever is new—the current composition. Afternoons are for naps and letters. Evenings are for reading, family, Red Sox

games on TV, and any revisions that just cannot wait. Basically, mornings are my prime writing time.

Once I start work on a project, I don’t stop and I don’t slow down unless I absolutely have to. If I don’t write every day, the characters begin to stale off in my mind—they begin to seem like characters instead of real people. The tale’s narrative cutting edge starts to rust and I begin to lose my hold on the story’s plot and pace. Worst of all, the excitement of spinning something new begins to fade. The work starts to feel like work, and for most writers that is the smooch of death. Writing is at its best—always, always, always—when it is a kind of inspired play for the writer. I can write in cold blood if I have to, but I like it best when it’s fresh and almost too

hot to handle.

I used to be faster than I am now; one of my books (TheRunning Man) was written in a single week, an accomplishment John Creasey would perhaps have appreciated (although

I have read that Creasey wrote several of his mysteries in two days). I think it was quitting smoking that slowed me down; nicotine is a great synapse enhancer. The problem, of course,

is that it’s killing you at the same time it’s helping you compose.

Still, I believe the first draft of a book—even a long one—should take no more than three months, the length of a season. Any longer and—for me, at least—the story begins

to take on an odd foreign feel, like a dispatch from the Romanian Department of Public Affairs, or something broadcast on high-band shortwave during a period of severe sunspot

activity.

I like to get ten pages a day, which amounts to 2,000 words. That’s 180,000 words over a three-month span, a goodish length for a book—something in which the reader can get happily lost, if the tale is done well and stays fresh. On some days those ten pages come easily; I’m up and out

and doing errands by eleven-thirty in the morning, perky as a rat in liverwurst. More frequently, as I grow older, I find myself eating lunch at my desk and finishing the day’s work

around one-thirty in the afternoon. Sometimes, when the words come hard, I’m still fiddling around at teatime. Either way is fine with me, but only under dire circumstances do I

allow myself to shut down before I get my 2,000 words.

-6-

Consider John Grisham’s breakout novel, The Firm. In this story, a young lawyer discovers that his first job, which seemed too good to be true, really is—he’s working for the Mafia.

Suspenseful, involving, and paced at breakneck speed, The Firm sold roughly nine gazillion copies. What seemed to fascinate its audience was the moral dilemma in which the

young lawyer finds himself: working for the mob is bad, no argument there, but the frocking pay is great! You can drive a Beemer, and that’s just for openers!

Audiences also enjoyed the lawyer’s resourceful efforts to extricate himself from his dilemma. It might not be the way most people would behave, and the deus ex machina clanks

pretty steadily in the last fifty pages, but it is the way most of us would like to behave. And wouldn’t we also like to have a deus ex machina in our lives?

Although I don’t know for sure, I’d bet my dog and lot that John Grisham never worked for the mob. All of that is total fabrication (and total fabrication is the fiction-writer’s

purest delight). He was once a young lawyer, though, and he has clearly forgotten none of the struggle. Nor has he forgotten the location of the various financial pitfalls and honeytraps

that make the field of corporate law so difficult. Using plainspun humor as a brilliant counterpoint and never substituting cant for story, he sketches a world of Darwinian

struggle where all the savages wear three-piece suits. And—here’s the good part—this is a world impossible not to believe.

Grisham has been there, spied out the land and the enemy positions, and brought back a full report. He told the truth of what he knew, and for that if nothing else, he deserves

every buck The Firm made.

-7-

A strong enough situation renders the whole question of plot moot, which is fine with me. The most interesting situations can usually be expressed as a What-if question: What if vampires invaded a small New England village? (’Salem’s Lot)

What if a policeman in a remote Nevada town went

berserk and started killing everyone in sight? (Desperation)

What if a cleaning woman suspected of a murder she got

away with (her husband) fell under suspicion for a murder

she did not commit (her employer)? (Dolores Claiborne)

What if a young mother and her son became trapped in

their stalled car by a rabid dog? (Cujo)

-8-

H. P. Lovecraft was a genius when it came to tales of the macabre, but a terrible dialogue writer. He seems to have known it, too, because in the millions of words of fiction he wrote, fewer than five thousand are dialogue.

-9-

Everything I’ve said about dialogue applies to building characters in fiction. The job boils down to two things: paying attention to how the real people around you behave and then

telling the truth about what you see. You may notice that your next-door neighbor picks his nose when he thinks no one is looking. This is a great detail, but noting it does you

no good as a writer unless you’re willing to dump it into a story at some point.

-10-

So far, so good. Now let’s talk about revising the work—how much and how many drafts? For me the answer has always been two drafts and a polish (with the advent of wordprocessing

technology, my polishes have become closer to a third draft). You should realize that I’m only talking about my own personal mode of writing here; in actual practice, rewriting varies

greatly from writer to writer. Kurt Vonnegut, for example, rewrote each page of his novels until he got them exactly the way he wanted them. The result was days when he might

only manage a page or two of finished copy (and the wastebasket would be full of crumpled, rejected page seventy-ones and seventy-twos), but when the manuscript was finished, the

book was finished, by gum. You could set it in type. Yet I think certain things hold true for most writers, and those are the ones I want to talk about now. If you’ve been writing awhile,

you won’t need me to help you much with this part; you’ll have your own established routine. If you’re a beginner, though, let me urge that you take your story through at least two drafts; the one you do with the study door closed and the one you do with it open.

-11-

These are the best books I’ve read over the last three or four years, the period during which I wrote The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon, Hearts in Atlantis, On Writing, and the as-yet-unpublished From a Buick Eight. In some way or other, I suspect each book in the

list had an influence on the books I wrote.

Abrahams, Peter: A Perfect Crime

Abrahams, Peter: Lights Out

Abrahams, Peter: Pressure Drop

Abrahams, Peter: Revolution #9

Agee, James: A Death in the Family

Bakis, Kirsten: Lives of the Monster Dogs

Barker, Pat: Regeneration

Barker, Pat: The Eye in the Door

Barker, Pat: The Ghost Road

Bausch, Richard: In the Night Season

Blauner, Peter: The Intruder

Bowles, Paul: The Sheltering Sky

Boyle, T. Coraghessan: The Tortilla Curtain

Bryson, Bill: A Walk in the Woods

Buckley, Christopher: Thank You for Smoking

Carver, Raymond: Where I’m Calling From

Chabon, Michael: Werewolves in Their Youth

Chorlton, Windsor: Latitude Zero

Connelly, Michael: The Poet

Conrad, Joseph: Heart of Darkness

Constantine, K. C.: Family Values

DeLillo, Don: Underworld

DeMille, Nelson: Cathedral

DeMille, Nelson: The Gold Coast

Dickens, Charles: Oliver Twist

Dobyns, Stephen: Common Carnage

Dobyns, Stephen: The Church of Dead Girls

Doyle, Roddy: The Woman Who Walked into Doors

Elkin, Stanley: The Dick Gibson Show

Faulkner, William: As I Lay Dying

Garland, Alex: The Beach

George, Elizabeth: Deception on His Mind

Gerritsen, Tess: Gravity

Golding, William: Lord of the Flies

Gray, Muriel: Furnace

Greene, Graham: A Gun for Sale (aka This Gun for Hire)

Greene, Graham: Our Man in Havana

Halberstam, David: The Fifties

Hamill, Pete: Why Sinatra Matters

Harris, Thomas: Hannibal

Haruf, Kent: Plainsong

Hoeg, Peter: Smilla’s Sense of Snow

Hunter, Stephen: Dirty White Boys

Ignatius, David: A Firing Offense

Irving, John: A Widow for One Year

Joyce, Graham: The Tooth Fairy

Judd, Alan: The Devil’s Own Work

Kahn, Roger: Good Enough to Dream

Karr, Mary: The Liars’ Club

Ketchum, Jack: Right to Life

King, Tabitha: Survivor

King, Tabitha: The Sky in the Water (unpublished)

Kingsolver, Barbara: The Poisonwood Bible

Krakauer, Jon: Into Thin Air

Lee, Harper: To Kill a Mockingbird

Lefkowitz, Bernard: Our Guys

Little, Bentley: The Ignored

Maclean, Norman: A River Runs Through It and Other Stories

Maugham, W. Somerset: The Moon and Sixpence

McCarthy, Cormac: Cities of the Plain

McCarthy, Cormac: The Crossing

McCourt, Frank: Angela’s Ashes

McDermott, Alice: Charming Billy

McDevitt, Jack: Ancient Shores

McEwan, Ian: Enduring Love

McEwan, Ian: The Cement Garden

McMurtry, Larry: Dead Man’s Walk

McMurtry, Larry, and Diana Ossana: Zeke and Ned

Miller, Walter M.: A Canticle for Leibowitz

Oates, Joyce Carol: Zombie

O’Brien, Tim: In the Lake of the Woods

O’Nan, Stewart: The Speed Queen

Ondaatje, Michael: The English Patient

Patterson, Richard North: No Safe Place

Price, Richard: Freedomland

Proulx, Annie: Close Range: Wyoming Stories

Proulx, Annie: The Shipping News

Quindlen, Anna: One True Thing

Rendell, Ruth: A Sight for Sore Eyes

Robinson, Frank M.: Waiting

Rowling, J. K.: Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Rowling, J. K.: Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azakaban

Rowling, J. K.: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

Russo, Richard: Mohawk

Schwartz, John Burnham: Reservation Road

Seth, Vikram: A Suitable Boy

Shaw, Irwin: The Young Lions

Slotkin, Richard: The Crater

Smith, Dinitia: The Illusionist

Spencer, Scott: Men in Black

Stegner, Wallace: Joe Hill

Tartt, Donna: The Secret History

Tyler, Anne: A Patchwork Planet

Vonnegut, Kurt: Hocus Pocus

Waugh, Evelyn: Brideshead Revisited

Westlake, Donald E.: The Ax

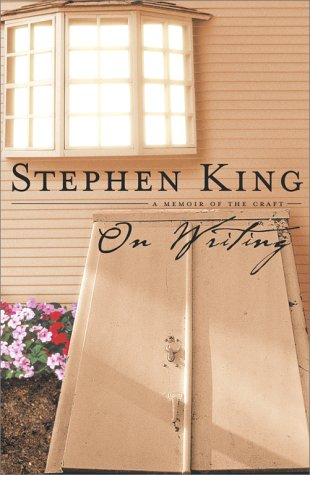

Stephen King - On Writing A Memoir Of The Craft (2000).

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق